1953

In Search of a Life, New Delhi

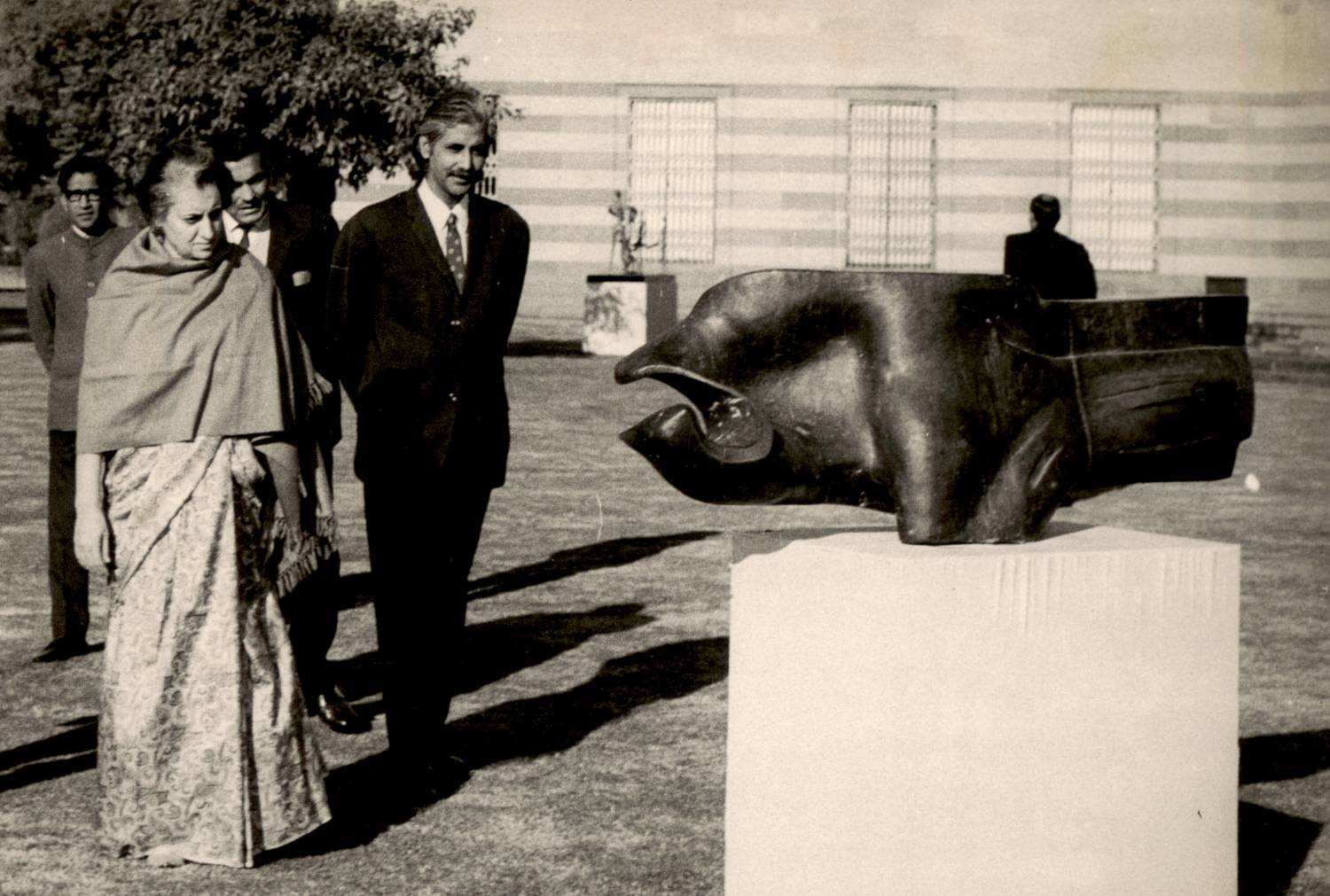

Before moving to India and securing a teaching job in India, Sehgal travelled extensively in Africa. He began working as an art teacher at the Modern School, New Delhi, while he continued to work on his own sculptures. At his open-air exhibition in 1954 on the school grounds, he received both criticism and acclaim for breaking convention in his display of the artistic form.

This is where he met his wife, Shukla, who was a teacher of English and science and went on to become his most honest but trusted critic and a firm supporter of his work. They were married in 1955 and have two sons.

He mapped the role of arts, crafts and cultural activity in communities responsible for creative expression and economic development. These few years in community development brought to his attention the real need for progress in agriculture and education, which further influenced his creativity. He believed the tradition of inheriting design, colour and form from the forefathers should be protected even while teaching new techniques and adding functionality to preserving the folk arts. In the process, there was an osmosis of craft. While Sehgal worked with grassroot communities, he learned more about traditional art and livelihoods that influenced his sculptures. He closely studied rural habitats and agricultural ecosystems. Farmers’ struggles, poverty and hunger were issues that deeply affected him. He urged the Planning Commission to rectify the damage caused by the neglect of the Colonial rule.

The mural designed by Sehgal at the Vigyan Bhawan, a prominent international convention hall, was a mammoth project both in size and relevance.

The 40ft x 140ft mural took five years to make and won widespread acclaim for depicting the ‘real’ India. It became a landmark in the cultural life of the city. Sadly, twenty years later, the piece was mutilated, and the government was taken to court for its lack of concern and redressal.

In a battle that lasted thirteen years, Amar Nath Sehgal vs the Union of India, illustrates the importance of the Copyright Act. Over the course of this long-standing fight, Sehgal questioned for the first time an artist’s involvement in the afterlife of their artwork, the intricacy of artists’ rights and the civic responsibility of the public in maintaining art as well as the role of authority. The case took a lot from him in terms of energy and agility, but following his success, attention was finally given to the moral rights of authors and was declared a landmark case by the judge.

He was a keen documenter, collecting and preserving photographs and literature from his shows around the world. He was a published poet in two languages. Perhaps it is the malleability of his materials and his own sensitive, susceptible nature that gave him the freedom to truly create. He consistently challenged himself through his craft.

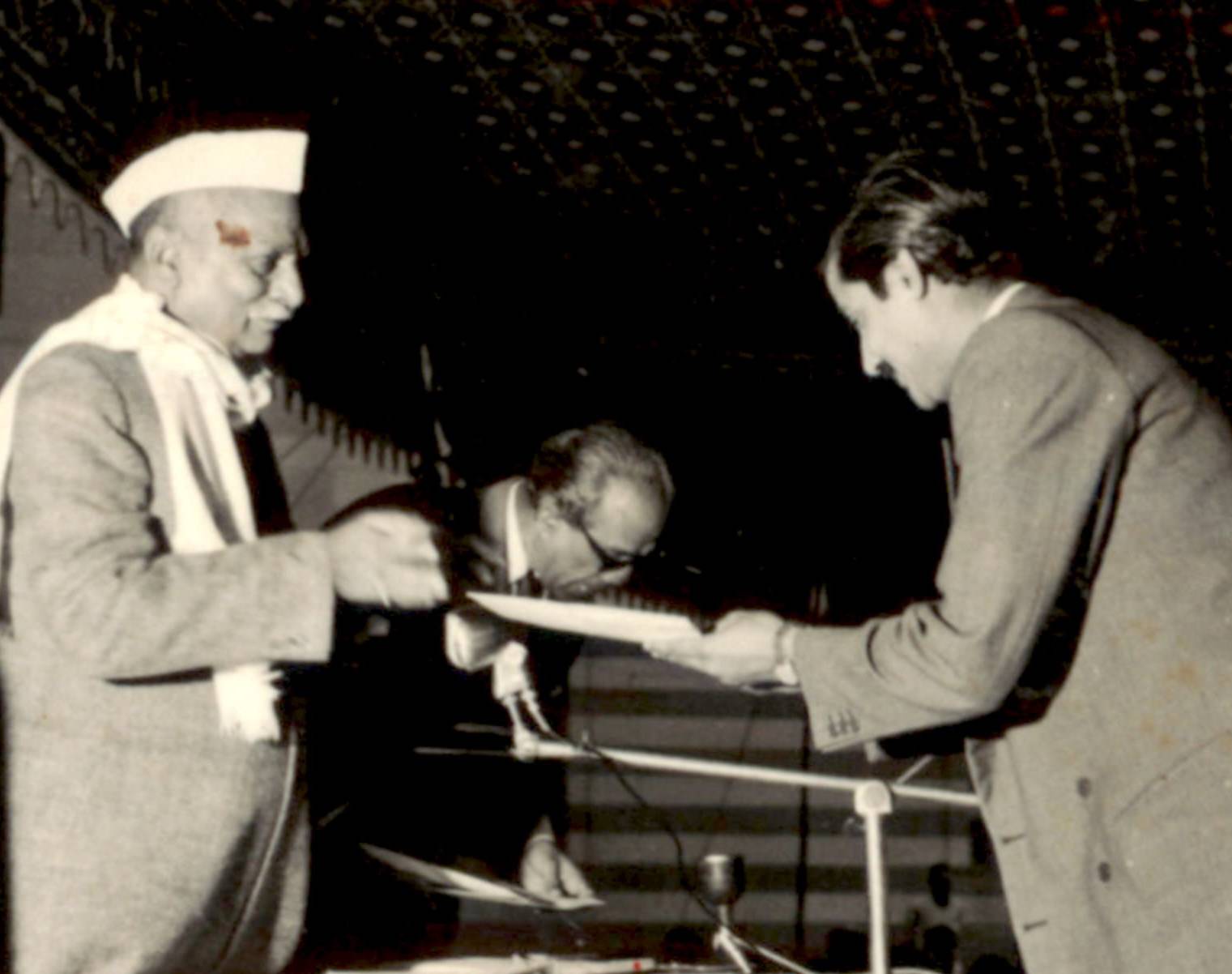

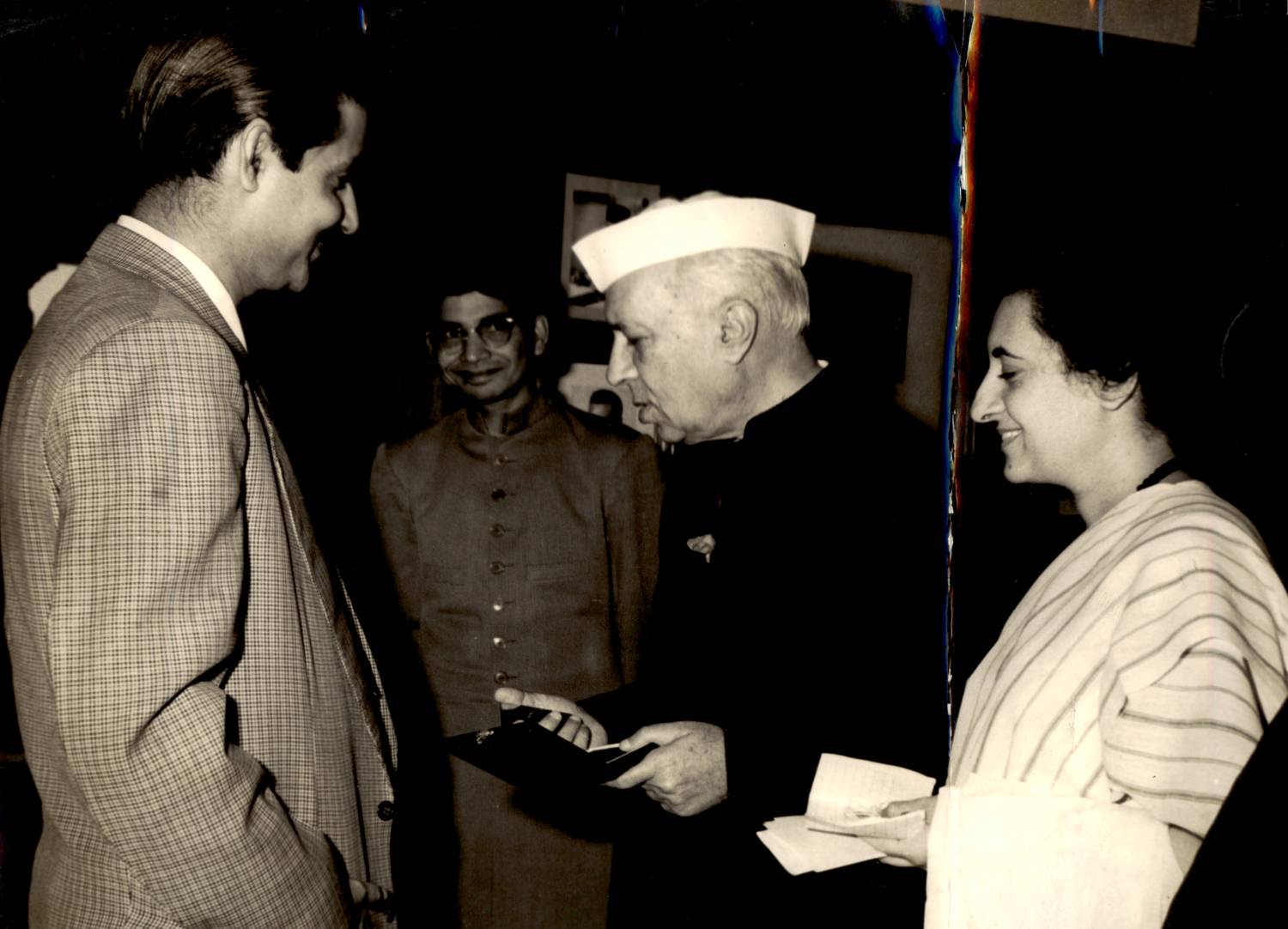

Over the course of his professional life, Sehgal had close to forty exhibitions, most of which were international participations. Sehgal’s excellence in form and prowess with technique continued to evolve till the end of his life, so much so it won him the prestigious Padma Bhushan Award after he passed. The onset of Parkinson’s disease and the crutch of old age could not stop him from creating prolifically, even in the last years of his life. His art continues to serve him as an eternal companion.